|

Race and secession

In the 1930s Western Australia was overwhelmingly white and British.

Small populations of Asians and Europeans from non-English speaking backgrounds

lived in areas of the State. Racism was endemic. Children endured school

yard taunts, families were excluded from community activities, adults were

denied the right to vote and, in extreme cases, acts of racial violence

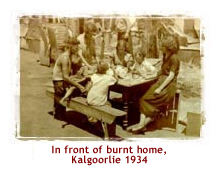

were taken against whole communities. In the goldfields the belief that

'foreigners' were taking the jobs of English-speaking Australians led to

severe racial tensions. The race riots of 1934 which resulted saw Kalgoorlie's

Italian and Yugoslav residents attacked, their businesses destroyed and

their homes burnt.

In the 1930s Western Australia was overwhelmingly white and British.

Small populations of Asians and Europeans from non-English speaking backgrounds

lived in areas of the State. Racism was endemic. Children endured school

yard taunts, families were excluded from community activities, adults were

denied the right to vote and, in extreme cases, acts of racial violence

were taken against whole communities. In the goldfields the belief that

'foreigners' were taking the jobs of English-speaking Australians led to

severe racial tensions. The race riots of 1934 which resulted saw Kalgoorlie's

Italian and Yugoslav residents attacked, their businesses destroyed and

their homes burnt.

Yet for all the hardships faced by these groups, Western Australia's Aboriginal

people endured the most oppressive discrimination, the result of racism,

indifference and well-intentioned meddling. Government policy imposed assimilation

through a native settlement scheme which removed 'half-castes' from their

families and taught them the 'white man's ways'. Efforts by the white community

to segregate Aboriginals in 'town reserves' - many towns through the south

west were declared off-limits - also placed Aboriginals in appalling living

conditions with malnutrition, disease, poverty and unemployment.

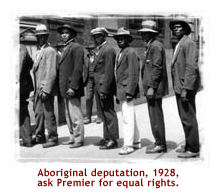

In 1928 a delegation of Aborigines met with Premier Philip Collier to protest

the unjust and repressive laws under which they lived. Although receiving

a sympathetic response from sections of the press, they were unsuccessful.

In 1936 the Native Administration Bill, updating the 1905 Act, gave even

greater powers to the Chief Protector of Aborigines, Mr A.O. Neville. These

were carried out in his name by local police. The Bill extended definitions

of who would be considered a 'native' to include all Aboriginal people except

'quadroons' - one fourth Aboriginal - over the age of 21 and 'octaroons'

- one eighth Aboriginal - thereby depriving many people of mixed descent

the right to conduct their own affairs. Travel, work, the income derived

from work, the ability to live in any location, to frequent public places

like hotels, and to raise families free from interference, were all denied

Aboriginal people of the 1930s.

As with Asian and non-English residents, the issue of secession meant little

to Aboriginal Western Australians.

|

|