Shark Bay

The French vessel Uranie arrived in Shark Bay on the Western Australian coast on 12 September 1818. The crew was greeted by the extraordinary sight of a great number of whales frolicking on the surface of the water, leaping into the air and churning up the sea. Nobody seemed particularly impressed otherwise by the prospects offered by the west coast of New Holland. Jacques Arago described the view of the land as offering "an image of nothing but desolation; no stream to relieve the eyes, no tree to attract them, no mountain varies the landscape, no dwelling enlivens it; everywhere aridity and death."

Paul Gaimard was very excited about the prospects of meeting some of the local inhabitants; "we are going to see man in a state of nature," he wrote, "savages, beings far removed from all civilisation; we will try to examine them closely, establish a relationship between them and ourselves, to converse with them by way of gestures, to guess, if possible, the reaction they feel upon seeing us; we will present them with gifts and think ourselves fortunate if we manage to obtain in exchange for our mirrors, knives etc, some of their weapons, fishing equipment etc."

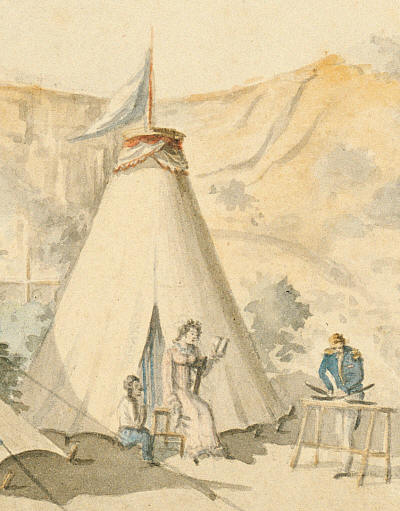

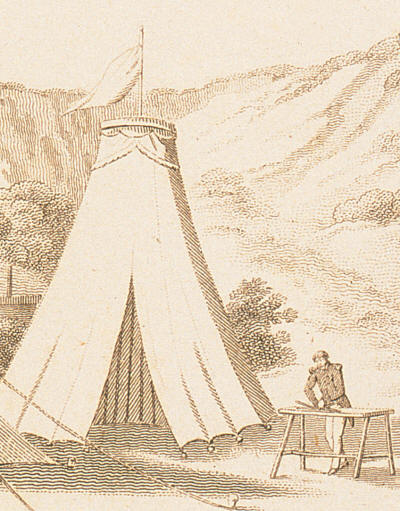

Above: The alembic being used to desalinate seawater in Shark Bay in 1818

(portion of a larger drawing, shown further below)

Freycinet's priorities for the camp ashore in Shark Bay were to set

up the alembic (a still for desalinating water) and an observatory.

The Uranie had arrived at the coast of New Holland with no fresh

water in the hold and, although an alembic had already been set up

on board, Freycinet thought that it would be prudent to start

desalinating water for their next passage. He tasked Gaudichaud, the

expedition's pharmacist and botanist, with setting up a second

alembic ashore. The west coast of New Holland was the only place on

the voyage that the expedition had need of the alembic because the

crew did not manage to find any fresh water on Peron Peninsula. The

Académie des Sciences later reported that "the crew, composed of 120

men, drank for a month nothing but the water provided by the

alembic; nobody complained or was bothered by it. … One can see,

following this interesting experiment, how desirable it is that

physicians and builders concern themselves with the best ways of

installing alembics aboard ships."

The observatory was set up in Shark Bay in order to collect data for the expedition's principle areas of research: the "figure" of the globe (the precise shape of the Earth); the Earth's magnetic field; and, to a lesser extent, meteorology. Data for the first area of research, determining the shape of the Earth, was collected using pendulums. "The figure of the Earth," stated the report of the Académie des Sciences, "can be deduced by comparing the number of oscillations made in 24 hours by the same pendulum in diverse latitudes." The second area of interest for the voyage was to establish an understanding of magnetic phenomena. It was understood that the declination of a magnetised needle underwent very small alterations each year and to understand this phenomenon readings and astronomical observations needed to be done in different places over the globe.

On 14 September, Freycinet sent a boat ashore under the command of lieutenant Labiche, loaded with the distilling equipment, tents and everything necessary to establish a temporary observatory. Landing was made difficult by sand banks and the boat ran aground before reaching the shore, forcing the crew to get out into the water. The boat did not reach shore until 11.30 at night, by which time everyone on board was very cold. The next day the shore party set to work collecting materials to set up the camp.

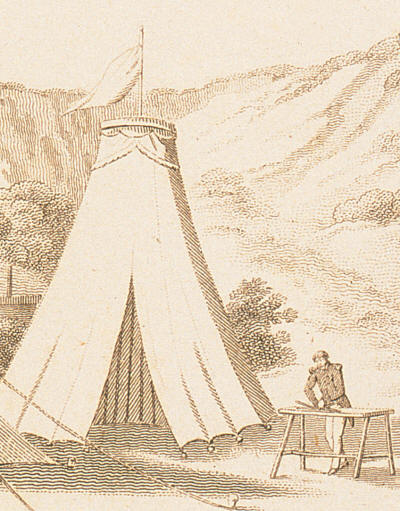

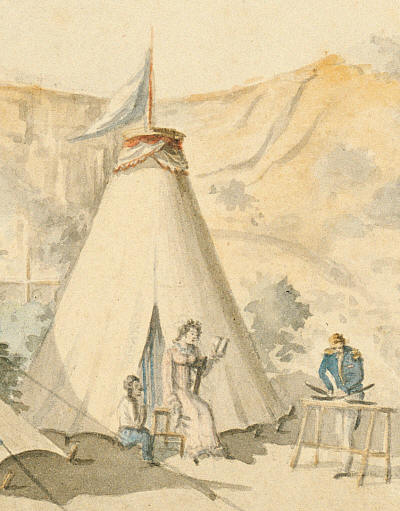

The most intriguing feature of the above watercolour by Pellion is the presence of Rose de Freycinet. Because Rose was a stowaway, and not part of the official crew, her image had to be removed for the official version of events. Also removed from the picture is a small boy who had come on board in Mauritius. Rose's sojourn in Shark Bay was not a particularly happy one. "That stay on land was not a pleasant one for me, the country being entirely devoid of trees and vegetation," she wrote. However she did, when it was not too hot, go looking for shells, of which she had amassed an impressive collection.

Above: Rose de Freycinet at the camp in Shark Bay in 1818 (left) and the official etching (right)

Both Arago and Gaimard expressed concern for the nutritional value

of the diet of the local Aboriginal people, and recount that,

amongst the objects left for the local inhabitants in an abandoned

camp were several knives which they had inserted into some oyster

shells as an indication of how they could be used because, as

Gaimard noted, "everything suggests that [the Aboriginals] are not

familiar with this source of food which is so abundant on their

shores." Given that the party's contact with the local inhabitants

of Shark Bay had been limited, the Frenchmen were both relying on

their Eurocentric preconceptions of the Aboriginal people as

child-like, uncivilised and unintelligent, and were completely

underestimating their detailed and intimate knowledge of the

landscape which had been their home since time immemorial.

Another noteworthy element of the images is the number of firearms the camp was equipped with. These would have been useful for hunting game but also served as protection from perceived threats. As eager as the Frenchmen were to encounter the local inhabitants of Shark Bay, they were also very fearful of an attack on their camp. Indeed, Freycinet's map of the area from the Baudin expedition shows that he had named the bay on the north-eastern tip of Peron Peninsula "Baie de l'Attaque". In 1801, sub-lieutenant Saint Cricq and the mineralogist Bailly from the Naturaliste had gone ashore where they were threatened by some 30 Aboriginal people armed with spears. Saint Cricq frightened them away by shooting into the air.

The crew of the Uranie had a more pacific encounter with the local people of Shark Bay. On 15 September Pellion, who was in charge of the camp, was informed of the presence of nine Aboriginals on the ridge behind their camp. Pellion immediately anticipated an attack and he and Gaudichaud prepared their weapons for self-defence, agreeing not to open fire except as a last resort. The Aboriginal people were armed, shouting, and pointing at the Uranie, making it clear that they wanted the Frenchmen to go back to their ship. Not sure how to assure the local inhabitants of their friendly intentions, the Frenchmen danced in a circle, causing much mirth among the Aboriginals, some of whom imitated the dance of the Frenchmen. After some negotiation through gesture, the Frenchmen offered some gifts, including a bottle of water and wine, some bacon, a piece of tin plate, glass jewellery and mirrors. Pellion offered a coloured scarf and in return was given a spear and another weapon. In spite of the exhortations of the Frenchmen to approach them, the Aboriginal men, and one woman carrying a child, kept their distance the whole time. When Arago arrived on the scene he played his castanets, to which some of the Aboriginal men responded by tapping with their spears while another danced. He also pretended to drink some salt water and concluded that, as the Aboriginals showed no sign of surprise upon seeing this, they must drink sea water to survive. At sunset the Aboriginal men left, indicating that they would return the next day. Pellion described them in the official account as "more deserving of pity than of any other sentiment."

Included in the instructions given to the ship's naturalists by the Académie des Sciences was a list of observations to carry out in relation to the native populations of the locations visited by the expedition. Paul Gaimard, having been on board the Uranie at the time the local Aboriginals visited the camp, was disappointed that he had missed seeing them. Eager to meet some of the locals himself, he set off with three other men and became lost in the salt lakes and sand dunes of the peninsula for several days. Although he did not manage to find any people, he did see some of their huts and footprints in the sand whose measurements he recorded in his journal.

The French vessel Uranie arrived in Shark Bay on the Western Australian coast on 12 September 1818. The crew was greeted by the extraordinary sight of a great number of whales frolicking on the surface of the water, leaping into the air and churning up the sea. Nobody seemed particularly impressed otherwise by the prospects offered by the west coast of New Holland. Jacques Arago described the view of the land as offering "an image of nothing but desolation; no stream to relieve the eyes, no tree to attract them, no mountain varies the landscape, no dwelling enlivens it; everywhere aridity and death."

Paul Gaimard was very excited about the prospects of meeting some of the local inhabitants; "we are going to see man in a state of nature," he wrote, "savages, beings far removed from all civilisation; we will try to examine them closely, establish a relationship between them and ourselves, to converse with them by way of gestures, to guess, if possible, the reaction they feel upon seeing us; we will present them with gifts and think ourselves fortunate if we manage to obtain in exchange for our mirrors, knives etc, some of their weapons, fishing equipment etc."

Above: The alembic being used to desalinate seawater in Shark Bay in 1818

(portion of a larger drawing, shown further below)

The observatory was set up in Shark Bay in order to collect data for the expedition's principle areas of research: the "figure" of the globe (the precise shape of the Earth); the Earth's magnetic field; and, to a lesser extent, meteorology. Data for the first area of research, determining the shape of the Earth, was collected using pendulums. "The figure of the Earth," stated the report of the Académie des Sciences, "can be deduced by comparing the number of oscillations made in 24 hours by the same pendulum in diverse latitudes." The second area of interest for the voyage was to establish an understanding of magnetic phenomena. It was understood that the declination of a magnetised needle underwent very small alterations each year and to understand this phenomenon readings and astronomical observations needed to be done in different places over the globe.

On 14 September, Freycinet sent a boat ashore under the command of lieutenant Labiche, loaded with the distilling equipment, tents and everything necessary to establish a temporary observatory. Landing was made difficult by sand banks and the boat ran aground before reaching the shore, forcing the crew to get out into the water. The boat did not reach shore until 11.30 at night, by which time everyone on board was very cold. The next day the shore party set to work collecting materials to set up the camp.

Above: Watercolour and ink drawing of camp at

Shark Bay, by J. Alphonse Pellion in 1818

click here for full zoomable drawing

In the lower left-hand corner of the watercolour image are two men

returning to the camp with a load of what appears to be oysters.

Jacques Arago recounts that at low tide on the 16th, he and some of

the sailors went in search of oysters that were plentiful on the

reefs of the bay. The oysters that the crew of the Uranie collected

and ate in Shark Bay are one of the few elements of that location to

earn any approbation from the French expedition. Gaimard described

them as having such a delicate taste that gastronomes of Cancale (a

town in Brittany famous for its oysters) would not have scorned

them. Rose de Freycinet claimed them to be "far tastier than all

those I had eaten, sitting at a table in comfort, in Paris."click here for full zoomable drawing

The most intriguing feature of the above watercolour by Pellion is the presence of Rose de Freycinet. Because Rose was a stowaway, and not part of the official crew, her image had to be removed for the official version of events. Also removed from the picture is a small boy who had come on board in Mauritius. Rose's sojourn in Shark Bay was not a particularly happy one. "That stay on land was not a pleasant one for me, the country being entirely devoid of trees and vegetation," she wrote. However she did, when it was not too hot, go looking for shells, of which she had amassed an impressive collection.

Above: Rose de Freycinet at the camp in Shark Bay in 1818 (left) and the official etching (right)

Another noteworthy element of the images is the number of firearms the camp was equipped with. These would have been useful for hunting game but also served as protection from perceived threats. As eager as the Frenchmen were to encounter the local inhabitants of Shark Bay, they were also very fearful of an attack on their camp. Indeed, Freycinet's map of the area from the Baudin expedition shows that he had named the bay on the north-eastern tip of Peron Peninsula "Baie de l'Attaque". In 1801, sub-lieutenant Saint Cricq and the mineralogist Bailly from the Naturaliste had gone ashore where they were threatened by some 30 Aboriginal people armed with spears. Saint Cricq frightened them away by shooting into the air.

The crew of the Uranie had a more pacific encounter with the local people of Shark Bay. On 15 September Pellion, who was in charge of the camp, was informed of the presence of nine Aboriginals on the ridge behind their camp. Pellion immediately anticipated an attack and he and Gaudichaud prepared their weapons for self-defence, agreeing not to open fire except as a last resort. The Aboriginal people were armed, shouting, and pointing at the Uranie, making it clear that they wanted the Frenchmen to go back to their ship. Not sure how to assure the local inhabitants of their friendly intentions, the Frenchmen danced in a circle, causing much mirth among the Aboriginals, some of whom imitated the dance of the Frenchmen. After some negotiation through gesture, the Frenchmen offered some gifts, including a bottle of water and wine, some bacon, a piece of tin plate, glass jewellery and mirrors. Pellion offered a coloured scarf and in return was given a spear and another weapon. In spite of the exhortations of the Frenchmen to approach them, the Aboriginal men, and one woman carrying a child, kept their distance the whole time. When Arago arrived on the scene he played his castanets, to which some of the Aboriginal men responded by tapping with their spears while another danced. He also pretended to drink some salt water and concluded that, as the Aboriginals showed no sign of surprise upon seeing this, they must drink sea water to survive. At sunset the Aboriginal men left, indicating that they would return the next day. Pellion described them in the official account as "more deserving of pity than of any other sentiment."

Included in the instructions given to the ship's naturalists by the Académie des Sciences was a list of observations to carry out in relation to the native populations of the locations visited by the expedition. Paul Gaimard, having been on board the Uranie at the time the local Aboriginals visited the camp, was disappointed that he had missed seeing them. Eager to meet some of the locals himself, he set off with three other men and became lost in the salt lakes and sand dunes of the peninsula for several days. Although he did not manage to find any people, he did see some of their huts and footprints in the sand whose measurements he recorded in his journal.

Above: Sketch of an Aboriginal hut at Shark Bay,

drawn in Paul Gaimard's journal in 1818

In 2014, as part of the project to create this website, the Shark

Bay

portion of Paul Gaimard's journal was transcribed and translated. For the first time, since being

written 196 years earlier, it can now be read in English - see

Gaimard's Journal.