Dirk Hartog Island

The part of the Western Australia coast where Shark Bay is located was known, at the time of the Freycinet expedition, as 'Eendrachtsland', or 'Terre d'Endracht'. In 1616 Dirk Hartog, master of the Dutch East India Company ship the Eendracht, had landed on the island in Shark Bay now named after him. There he left a record of his visit inscribed into a pewter plate which he attached to a wooden post. In 1697 Willem de Vlamingh discovered the Hartog plate and removed it, leaving a new plate, with the original Hartog inscription plus a record of his own visit, on a new post in the same location as the original.

During the Baudin expedition (1800-1804) Louis de Freycinet had been an officer on board the Naturaliste, under the command of Emmanuel Hamelin. During the Naturaliste's stay in Shark Bay in 1801, the explorers discovered the plate left by de Vlamingh, which had fallen off the post and was buried in the sand. Hamelin believed that to remove the plate from the island and take it back to Europe would amount to sacrilege, so the men of the Naturaliste nailed it to a new post and the place was named 'Cape Inscription'.

Freycinet did not share Hamelin's opinion regarding the removal of the de Vlamingh plate. "I did not have the same scruples” he wrote, in the account of the voyage he commanded 17 years later. Worried that such a fascinating object would once again become swallowed by the sand, or that careless sailors would destroy it, Freycinet believed that its rightful place was in a repository of scientific documents where it could be of use to historians. On 13 September 1818 he sent a party under the orders of midshipman Fabré to go to Dirk Hartog Island with the aim of establishing some geographical bearings, but also to retrieve the plate. With Fabré went midshipman Ferrand; Quoy the doctor, to make notes on the island in relation to natural history; and Adrien Taunay, to make illustrations.

The Dirk Hartog Island party searched Cape Inscription for the de Vlamingh plate and found it in the sand, the wooden post having disintegrated. They took the plate and returned (with some difficulty) aboard the Uranie. Jacques Arago recounted the joy that prevailed on board after the return of the party, which had been gone longer than expected and caused much worry aboard the Uranie. Arago noted, apparently with disapproval, that they had succeeded in bringing back the plate: "I will refrain from comment" he wrote in his account. Freycinet presented the plate, in March 1821, to the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, one of the five academies of the Institut de France.

Probably improperly catalogued, the de Vlamingh plate was lost in the archives of the Institut until 1940 when it was found in a storeroom. In 1947 the plate was presented by the French Ambassador to Prime Minister Ben Chifley and returned to Western Australia. It is now housed at the Shipwrecks Gallery of the Maritime Museum in Fremantle.

The part of the Western Australia coast where Shark Bay is located was known, at the time of the Freycinet expedition, as 'Eendrachtsland', or 'Terre d'Endracht'. In 1616 Dirk Hartog, master of the Dutch East India Company ship the Eendracht, had landed on the island in Shark Bay now named after him. There he left a record of his visit inscribed into a pewter plate which he attached to a wooden post. In 1697 Willem de Vlamingh discovered the Hartog plate and removed it, leaving a new plate, with the original Hartog inscription plus a record of his own visit, on a new post in the same location as the original.

During the Baudin expedition (1800-1804) Louis de Freycinet had been an officer on board the Naturaliste, under the command of Emmanuel Hamelin. During the Naturaliste's stay in Shark Bay in 1801, the explorers discovered the plate left by de Vlamingh, which had fallen off the post and was buried in the sand. Hamelin believed that to remove the plate from the island and take it back to Europe would amount to sacrilege, so the men of the Naturaliste nailed it to a new post and the place was named 'Cape Inscription'.

Freycinet did not share Hamelin's opinion regarding the removal of the de Vlamingh plate. "I did not have the same scruples” he wrote, in the account of the voyage he commanded 17 years later. Worried that such a fascinating object would once again become swallowed by the sand, or that careless sailors would destroy it, Freycinet believed that its rightful place was in a repository of scientific documents where it could be of use to historians. On 13 September 1818 he sent a party under the orders of midshipman Fabré to go to Dirk Hartog Island with the aim of establishing some geographical bearings, but also to retrieve the plate. With Fabré went midshipman Ferrand; Quoy the doctor, to make notes on the island in relation to natural history; and Adrien Taunay, to make illustrations.

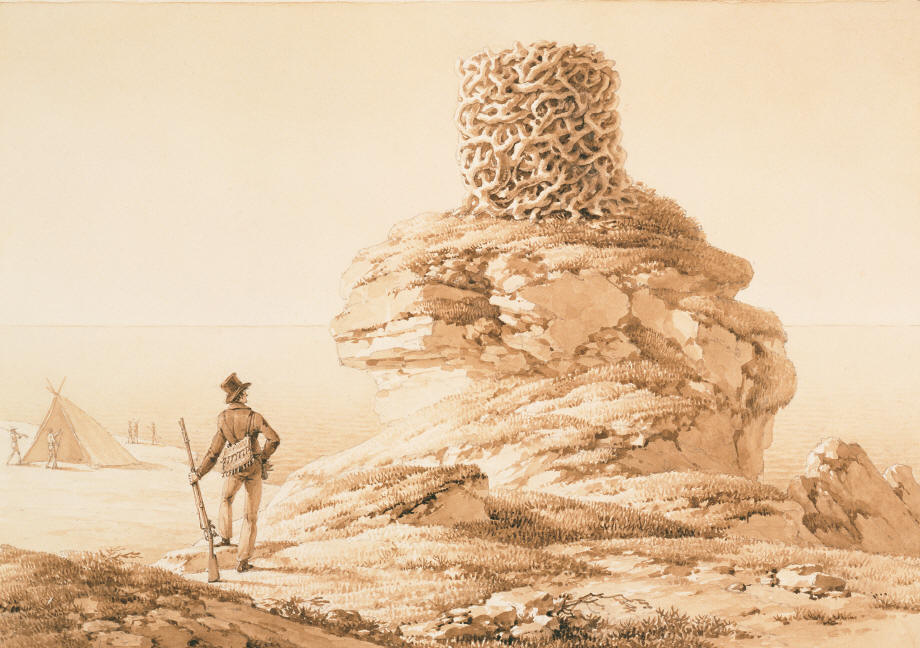

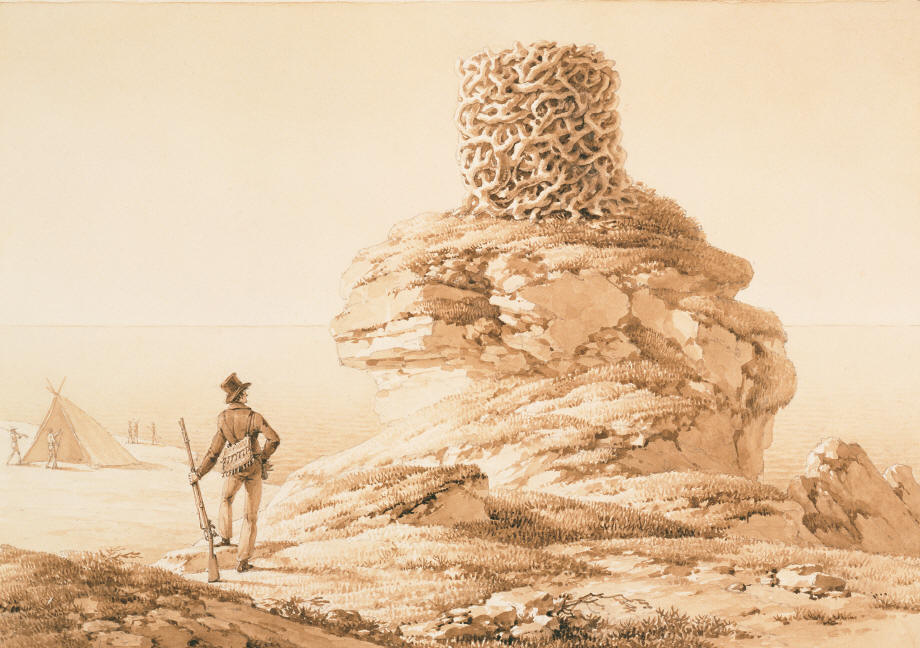

Pencil drawing of a gigantic bird’s nest on

Dirk Hartog Island, drawn by Adrien Taunay in 1818

Quoy reported that, on their way towards Cape Inscription, the party

came across a rocky outcrop on top of which they saw a sort of

rounded turret, six feet high, which was the nest of what he

described as a "goshawk" (autour in French, probably a white-bellied

sea eagle) with a white belly and a grey back. The nest, reported

Quoy, was constructed from dead mimosa branches and shallow enough

on the inside that the bird could look out over the side. In the

nest they found one fawn-coloured egg with brown speckles, about the

size of a chicken's egg. The base of the rock was covered in animal

bones and the debris of fish, reptiles and crustaceans.The Dirk Hartog Island party searched Cape Inscription for the de Vlamingh plate and found it in the sand, the wooden post having disintegrated. They took the plate and returned (with some difficulty) aboard the Uranie. Jacques Arago recounted the joy that prevailed on board after the return of the party, which had been gone longer than expected and caused much worry aboard the Uranie. Arago noted, apparently with disapproval, that they had succeeded in bringing back the plate: "I will refrain from comment" he wrote in his account. Freycinet presented the plate, in March 1821, to the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres, one of the five academies of the Institut de France.

Probably improperly catalogued, the de Vlamingh plate was lost in the archives of the Institut until 1940 when it was found in a storeroom. In 1947 the plate was presented by the French Ambassador to Prime Minister Ben Chifley and returned to Western Australia. It is now housed at the Shipwrecks Gallery of the Maritime Museum in Fremantle.